Nepotism is one of the oldest practices in the world. The term nepotismo originated in the 14th century to describe the corrupt practice by popes of appointing male relatives to cardinalates and other high positions in the church. It derives from the Latin root word nepos, meaning (in my Snoop Dogg voice) “nephew.” Throughout history, many Asian dynasties have strived on nepotism, and though they no longer have any real political power, the British royal family has passed down royal reign for centuries. Nepotism has also been very prevalent in US political history. John Adams appointed his son, John Quincy Adams, as a diplomat, and after he was elected president in 1960, JFK appointed his younger brother, RFK, as attorney general. Successful businessmen have passed their empires down to their kids to take the reins once they’re gone (the Trumps, the Smurfits, the Murdochs, and the Mistrys, to name a few). The music industry may be the most notorious field for nepotism: Simon Cowell, Miley Cyrus, Willow and Jaden Smith, Enrique Iglesias, and many more have greatly benefited from nepotism. Busta Rhymes would also use nepotism to help his family, Rampage The Last Boy Scout.

Busta Rhymes and Rampage are first cousins. Before his solo career skyrocketed, Busta was in a group called Leaders of The New School. Busta was gracious enough to let Rampage jump on “Spontaneous” from LONS’ second album, T.I.M.E. Their kinship would also lead to Rampage opening up for LONS at shows, and when Busta went solo, it would lead to even more opportunities for Rampage. He’d make a few high-profile cameos (see Funkmaster Flex’s Volume 1: 60 Minute Of Funk, Craig Mack’s “Flava In Ya Ear (Remix),” and Busta’s debut album, The Coming), and eventually, it would lead to a record deal with Elektra, which was also Busta’s label home. Rampage released his debut album, Scout’s Honor…By Way Of Blood, in the summer of ‘97.

Most of Scout Honor’s production was handled by DJ Scratch (from EPMD fame) and Rashad Smith, who blessed Busta’s debut hit single, “Woo-Hah,” and later would become one of Puffy’s Hitmen. Despite three singles, decent reviews, and Busta’s backing, Scout’s Honor wouldn’t perform well commercially and came and went quicker than Flash Gordon getting cheeks from a prostitute, knowing that Ming The Merciless is closing in on him. It would be nearly a decade before Rampage would drop another album, fittingly titled Have You Seen? The album was released independently (Sure Shot Records), so not many knew of its existence, officially ending Rampage’s relevancy in hip-hop.

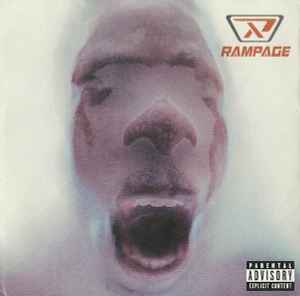

Scout’s Honor is another first-time listen for me, and if the music is anything near as wild as the album cover, this should be a colorful experience.

Intro – The album begins with a three-piece intro suite. First, Kau Kidau introduces Rampage via a bullhorn while complete chaos and destruction occur in the background. Then Rampage introduces himself over some hard Sparta/300-type shit. The last act features Storm hyping up Flipmode Squad and setting up the next record.

Flipmode Iz Da Squad – DJ Scratch serves up a dusty and triumphant boom-bap production for Rampage, Serious (who sounds like a whiny version of Greg Nice), Spliff Star, Busta Rhymes, and Lord Have Mercy to represent Flipmode. Besides Serious (whom I could not take for his name), they all sound competent (Busta? What the hell is an “end of the world nigga”?). It would have been nice to hear a Rah Digga verse over this dope instrumental (she wasn’t yet a part of Flipmode), but it’s still a solid record.

Da Night B4 My Shit Drop – The track begins with a cornball reporter asking our host questions about his forthcoming album (he pops up again between the verses). Then Rampage spits two verses describing his actions and mind state the night before his album’s released: “I’m sittin’ in the room, smokin’ a phat bag of boom, watchin’ a crazy cartoon, plus my hour’s coming soon, it’s a minute to midnight, I’m soon to take flight, I’m sounded right, sucka niggas can’t see my light, I’m nervous, ready, wanna know how I’m coming, The Boy Scout drop the true shit then I’m humming.” The rest of the song features more of Rampage speaking on his confidence, nervousness, and excitement surrounding the album. Props to Rampage for the unique song concept, and Rashad Smith’s backing instrumental is an irresistible banger. The record ends with two West Coast cats (C-Dog and his homeboy) chopping it up about Rampage’s album.

Talk Of The Town – Over crisp drums and a darkly emotional piano loop, Rampage big-ups himself, takes a subtle jab at Son of Bazerk (rip Almighty Jahwell), and shares one of his kinky fetishes with the listeners.

Get The Money And Dip – Scratch keeps the heat coming with a warped, soulful music bed. Our host navigates through it well, and Busta resurfaces to add some spice to the hook.

The Set Up – Rashad Smith gets his second production credit of the night. Rampage uses the creamily somber instrumental to break down the trials and tribulations of a rapper turned thug rapper, turned rapper and thug. It’s a classic tale of the power of the tongue, which I’m sure was inspired by the Tupac and Biggie tragedies (predicting what year someone will die, which Rampage (sort of) does to the subject of this song during the hook, is wild). Dope record. It’s followed by a skit of two White boys, S.O. and Dan-o-the-Mano, looking to get wild for the night on shrooms, but S.O.’s antics bring the evening to a premature end. I chuckle every time I listen to it.

Wild For Da Night – This was the album’s lead single. This time, Backspin The Vibe Chemist taps another dark piano loop to build the backdrop around, and Busta adds his animated energy to the hook. Busta also ends the record by issuing a warning to all “competitive muthafuckas” looking to challenge the Flipmode Squad.

Flipmode Enemy #1 – Rampage pays homage to Public Enemy and their classic record of the same name (replace “Flipmode” with “Public”). It’s followed by a hilarious skit about a booty call that ends in stinky fashion.

Take It To The Streets – This was the second single. Our host is ready to drink, smoke, have sex, and party, and Billy Lawrence joins in on the fun during the chorus and bridge (she was making her hip-hop rounds in ’97). Surely, this processed bullshit was contrived by the label, looking to score a crossover hit. I’m sure even Rampage hated this record. The track ends with a zany Sesame Street type ass whoopin’ skit.

Conquer Da World – Rampage is looking to become the Julius Caesar of hip-hop, and he gets a female vocalist named Meka to encourage him on the hook and adlibs. Ramp’s bars were adequate, but I was more impressed by DJ Scratch’s bassy soul vibes.

Hall Of Fame – Ramp spits a little bit on this record, but it’s far from Hall of Fame status (shout-out to New York Undercover and the Doobie Brothers). I love the mixture of creepy and gully in Scratch’s backdrop.

Niggaz Iz Bad – Serious returns to join Ramp on the mic and doesn’t fare much better than he did on the Flipmode posse joint early in the album. Apparently, this was recorded in ‘94 (there are at least two references made to the year in the song), but it still sounds cohesive with the rest of the album. Give Rashad Smith another pound for this dope beat.

We Getz Down (Remix) – The album closes with what would be the third and final single. Teddy Riley gets his lone production credit of the album, sampling the hypnotic bass line from Cameo’s “Strange” and turning it into a slick groove that Rampage glides through doing figure eights in boastful skates (it’s the same instrumental that plays in the background on the C-Dog skit early in the album). The record has remnants of crossover intent, but its G-funk sensibilities feel good, and it’s one of my favorite joints on Scout’s Honor.

Rampage Outro – Rampage shares a few parting words (which includes a shameless plug for his Flipmode leader and label mate Busta Rhymes’ forthcoming album, When Disaster Strikes) to wrap up the album.

In one season at USC, Bronny James averaged 4.8 points and 2.1 assists in the twenty-five games he played. Those are very mediocre stats, but when your dad’s name is LeBron James, and he makes it clear he wants to play on the same team as his son, those numbers become good enough to get you drafted by the Lakers in the second round of the 2024 NBA draft. During his rookie season, Bronny struggled, and when demoted to the G-League, the struggle continued. It was only his rookie year, so I’m not writing the young man off, but he clearly wasn’t ready for the NBA yet. Busta Rhymes also yielded his influence to get his cousin, Rampage, a deal with Elektra. Much like Bronny’s rookie campaign, Scout’s Honor wasn’t a commercial success, but was it because Rampage wasn’t ready for the big leagues?

The production on Scout’s Honor is damn near flawless. DJ Scratch and Rashad Smith lead and cultivate a sonically top-tier product, skillfully flipping dope soul, jazz, funk, and rock loops over durable drumbeats. Besides the godawful “Take It To The Streets,” it’s quintessential East Coast nineties boom bap. Unlike the production on Scout’s Honor, Rampage is not a top-tier emcee, but he’s proficient on the mic and moderately masters the ceremony throughout. Like his mentor (Busta Rhymes), Ramp rhymes (no pun) with charisma and can switch up his tone and delivery in a heartbeat as if he suffers from DID. There are a few magical microphone moments on the album when Rampage finds the perfect pocket, and his flow rides the beat like Zorro on Tornado (see the beginning of the opening verse on “Da Night B4 My Shit Drop” and “We Getz Down”). But most of Scout’s Honor finds its host spewing random freestyle rhymes that technically sound good but feel aimless and ring hollow.

On the album’s intro, Ramp overzealously says (or, more appropriately, yells), “I feel like I’m about to conquer the world!” Scout’s Honor is not world-conquering material. Nor is it a terrible project. In the annals of hip-hop, it should sit as a sturdy debut project from an emcee with potential who got his chance by way of blood.

-Deedub

Follow me on Instagram @damontimeisillmatic

Its so fascinating how Rashad Smith can do smooth and rugged shit like his other three tracks on here but then do the Take It To The Streets track on the same album. Obviously those other tracks were recorded before the latter (Set Up, ’95, Niggaz Is Bad, ’94), but it’s interesting how some producers (and rappers) made attempts to be chameleons with some of the major sonic shifts of that late 90s era.